|

| Bully Pulpit Games (Jesse Parrott) |

Durance thrusts player into a deep space prison colony on a hostile, barely understood world. They'll assume roles on both sides of the colony's power structure: its criminal populace and their rulers. Resources are scare, death is plentiful, and power regularly trades hands. An individual can rise through the ranks, but who's to say anything will be left to reign over. And who knows what they'll have to give up along the way...

Published by Bully Pulpit Games a few years after their hit roleplaying game Fiasco, 2012's Durance was also written by Jason Morningstar. Like its predecessor, Durance is a part of the new breed of "Rules Light Story Games," where complex mechanics and hours of prep are discarded for a wholly narrative experience. Rather appropriately for a game about hierarchy- and the way it changes - Durance has no Game Master. The closest it gets are the Host and Guides, the former who mostly just sets things up.

Players take turns as the Guide, passing off control clockwise each scene. They set up the scenario with a single question, which can be vague or specific - as long as it generates some conflict between two characters. The Host merely asks the occasional question to keep things on track.

With a setup like that, Durance gets as chaotic as you'd imagine. With no real GM and little in the way of rules, the only thing holding the show together are the shifting authorities of the prison colony. Durance relies almost entirely on improvisation and the good will of the players, leading to some of the more memorable sessions I've played. The focus on story and way it puts you on the spot also helps players get used to RPGs as a story rather than some sort of analog video game. Overall, it's more fun than you'd expect to have on a hostile world with no hope of escape.

No Such Thing as Paradise

In contrast with the almost nonexistent rules, Durance leans heavily into the atmosphere created by its setting. A spacefaring humanity struggles with the same old problems, taking the "humane" route with their excess criminals and ne'er-do-wells. Hurled across space to settle barely explored worlds, never to return. There's even the promise of freedom, though only the convicts' children will likely get to enjoy it. Unfortunately, out of an overenthusiasm or sheer apathy on the part of surveyors, the prison colonies are hardly being established on paradise worlds.

|

| Bully Pulpit Games (Brennen Reece) |

The characters, free and imprisoned alike, discover their promised fresh start is on a vicious, hostile world. That's hardly the circumstances for a more just, freer society and no one feels like playing nice. Injustice reigns across the newly settled stars and even authoritarian rulers and back breaking labor has failed to stamp out criminal empires. There's little cause for hope but that hasn't stopped a few from wanting it all.

Durance offers a setting with some clear rules and history but plenty of room for improv heavy roleplay. As much as I love my elaborate, interconnected game settings, that doesn't make broader but no less compelling settings any less appealing. The gameplay integration certainly helps that and leads to the most enjoyable mechanic. Kicking off every game is the Planetary Survey, a set of six facts about the planet's habitability. Players go around in a circle striking off a fact each, until only three of the ideal qualities are left.

The remaining facts match up with one of 19 pregenerated planets, with suitable names like "RFS 617" and "Amur's Folly." Players compare the world's pollyannic report with the harsh reality of the situation, along with 6 Details, story prompts to be used by the Guides when forming their questions.

The process is repeated for Colonial Records, generating an equally unappealing regime for the players to endure and/or profit from. In addition to another 6 Details, players are given the Authority's perspective on the colony, alongside the Convict's experience. As you could imagine, it hasn't been working out for either of them.

The numerous options add to the replayability, while selling the background and tone of the game better than winding paragraphs could. Players see what the colonists were sold was not the hardscrabble, industrial nightmare they received. It's an evocative text that immediately sets the stage, giving some very important guidance in a game where players are left largely to their own devices.

I am the Law

Each player receives two "Notables," one Convict and one Authority. Multiple characters are very uncommon, even for more unorthodox RPGs but a stroke of genius for Durance. As the book notes, it helps to have a backup when death looms so large. It also keeps players involved in the colony's constantly evolving story, which would otherwise be difficult without a traditional GM to keep the focus even. Most of all, having a character on both sides of the ladder lets players experience the full range of the colony's repressive social order, with the added bonus of keeping real world antagonism in check.

|

| Bully Pulpit Games (Jesse Parrott) |

In between that are the lieutenants, muscle, schemers, and comparatively normal folk. There's a range of roles to be filled, though the lack of any real heroes definitely stands out. Players can certainly choose to do the right thing but circumstances discourage it. Every Notable seeks the colony's unique Drive, chosen from six by process of elimination. Encompassing broad ideals like Control, Harmony and Freedom, every Notable has to balance their desire for the Drive with their Oaths, generated on a chart and fleshed out by the players.

Uncertain Times

When an Oath is broken, the change affects far more than just the Notable (who promptly fades into the background, potentially in lethal ways). A position on the Ladder shifts, part of the assessment changes, or the Drive even switches over. Character development plays a big role in Durance and a single person's decision can affect everyone.

|

| Bully Pulpit Games (Brennen Reece) |

Aside from that, there's hardly any dice rolling involved in actually playing Durance.

All the Rest

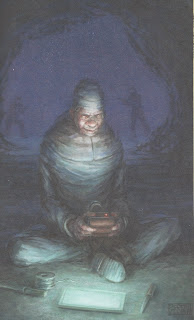

Despite the light ruleset, most of Durance's 133 page count is taken up by the mechanics, mainly the different planets and colonies. Much like the setting, there's no room for waste here. The game's lack of complexity hardly means a lack of thought was put to it. The many worlds of Durance feel fleshed out, a must for a game so open to interpretation. Evocative art from Brennen Reece and Jesse Parrotti further sells that. It's raw and sketchy, taking the form of journal illustrations, though the sense of humanity isn't lost in the rough. The same goes for the more detailed color pieces, which feel no less desperate - or sympathetic.

The book also briefly offers support for using Durance to roleplay its historical inspiration; 18th century Australia, recently colonized by the First Fleet. The parallels are apparent if uncomfortable in places. Playing space colonists obviously lacks the same historical weight as real world settlers. The author even concedes that's in poor taste to have aboriginal people slotted into the role of "hostile aliens." The offered defense, that the two groups might as well have been worlds apart, doesn't really justify it either. The real world also has far less room for improv, as reflected by the substantial Resources list of nonfiction books and wikipedia articles.

It does draw attention to one of the few real issues with Durance. Between the chaos of the game itself and the difficulty most players have with improv, it's not very sustainable. Things tend to go in a very disastrous very quickly. That's perfect for one shots but largely unsuitable for long term play, which you'd especially hope for after putting in the work for a historical game. Even then, you could argue that adds to the already strong level of immersion. Nothing was built to last in the prison colonies of Durance, so it's up to the players to make their mark before their time is up.